Late last year, I said you can get better. I argued this from a logical and evidential perspective. But I realize that such arguments alone can often be insufficient. Each of us views our situation as unique, because it is. When we are in the throes of depression or other mental health issues, we come up with our own, personal reasons for why statements like "you can get better" don't apply to us, that even the hardest of evidence cannot overcome.

I am not going to try to convince you out of that, because it is not a belief based in logic and evidence, so a logical and evidential response does nothing. Instead, I am going to argue why it is so necessary to believe that you can get better. At the end of this, I do not expect to convince you that you can get better. Believing that is your own choice.

===

At its core, recovery has a foundation of hope.

Hope is often viewed as a sketchy thing. It is, by definition, not based in a rational view of the world. Which is not to say that it is irrational, but that it has its domain in the realm of the future, whose outcome we do not know. We can guess what might happen, and sometimes those guesses can be very well-informed, but in the end, we're still at the mercy of uncertainty.

Uncertainty is the killer for many struggling with their mental health. Faced with a great unknown, our first instinct is to assume failure. We assume based on past experiences, past sufferings. We think to ourselves "things have been bad in the past, and things are bad now, so things will be bad in the future".

Recovery is about taking that line of thinking and rejecting it. It is about saying "things have been bad in the past, and things are bad now, but that does not mean they have to continue to be bad".

At any point in our life, misfortunes can occur. We can make mistakes. We can suffer tragedies through no fault of our own. We can face setbacks. At the same time, there is potential for our lives to improve. We may face an unexpected windfall. We may make the right decisions that pay off. We can better ourselves. Both outcomes are possible. They are not equally likely, but they are possible.

"You can get better" is a statement of faith. I say that not in a religious sense. I am not advocating for or against any belief system, save the one that says we can have a better life than the one we have at this moment. "You can get better" is making a statement about the future which we do not know, and cannot verify. It does not change the world. But it can change ourselves.

We can, if we so choose, believe that the worst outcomes will happen. We can believe that our lives will continue to stay bad, or get worse. If we do that, we run the risk of resigning ourselves to that outcome. If we believe that things will get worse, we deprive ourselves of motivation for trying to improve, because what is the point of trying to improve if things are only going to get worse? In that sense, believing things will get worse becomes a form of self-sabotage.

If, on the other hand, we believe that things can get better, we open ourselves to the possibility that they will. We direct our actions towards that possibility. Medication, therapy, improving our financial and social situation, these all become routes towards that possible bettering. They can help, because we believe that they can help.

Believing that things can get better does not mean that we are opening ourselves to false expectations. It does not mean that we are deluding ourselves that our outcome will be perfect, that we will achieve a utopian existence or some form of enlightenment. It doesn't mean that solutions will be easy. Such beliefs are as based in poor mental health and an irrational view of the world as the belief that we will only get worse, and is often the root of pseudosciences and scams that threaten to derail recovery attempts.

Recovery is long and it is onerous. It is not a straight road but a winding one full of potholes and detours and the risk of sudden mudslides. It involves trying out different medications and different therapists. It is about taking risks and taking the sometimes unpleasant results that come from those risks. It is about getting hurt, and moving on from that hurt.

If we go on that path, there is no guarantee that we will get better, because no guarantee exists. If we do not go on that path, however, we will most certainly not get better, because we did not even try.

===

So here is what I say:

I cannot make you believe that you can get better. There is no argument I can give that is so logically perfect that everyone will be convinced by it.

But I can say it, and you can choose to believe it.

There are no guarantees. There never are. Countless things can happen. But if you don't believe that things can get better, there is only one outcome.

But if you believe that things can get better, things can change. You open yourself up for the possibility of getting better.

I am talking about making a leap of faith. I am talking about putting your trust in a future you do not know. I am talking about believing in something even if you do not know that it is true. Not because it is true, but because you can gain so much by believing it.

I cannot say that you won't be hurt, because you will be. I cannot say you won't make mistakes, because you will. Life is hard. Life is full of struggles. This is as true for you as it is for everyone else.

What I say is that you can get better. You can still make it through.And you can choose to believe that.

FURTHER READING

Teaching Hope - A short overview of a Positive Psychology-based definition of hope and the benefits of health

The Wills And Ways Of Hope - A longer article describing hope and it's numerous benefits.

Perspectives on mental illness, self-therapy, and advice from one partly-broken thing to another.

Monday, March 31, 2014

Monday, March 24, 2014

The Importance Of Other People

Isolation does not mix well with mental health. Often mental illness can leads to ourselves spending a lot of time alone. Sometimes this is because the very effects of our mental illness make us not want to spend time with others, or enjoy spending time with others less. Sometimes this is because the content of our thoughts can be so strange and frightening that we feel like a pariah, and isolate ourselves from other, "normal" people, who we may be afraid of hurting, or afraid they may notice how we're feeling and avoid us.

Everyone is alone sometimes. Sometimes we need to be by ourselves for a while. For people with good mental health, being alone is not that much of a problem. For someone who struggles with mental issues, excessive isolation can be very problematic.

We are social creatures. Most of us thrive and depend upon the companionship of other people. We enjoy spending time with them, and they help us feel loved, and valuable. Often, they help keep our demons at bay by their presence alone, their own voices counteracting our own self-critical or otherwise problematic voices.

In the absence of people we can enjoy ourselves with, the only things we have to keep ourselves company are ourselves. And sometimes, we don't give ourselves the best company. Critical and negative voices in our head routinely attempt to beat us down. Obsessions make themselves known in our idle thoughts. The sheer knowledge of our own loneliness folds in on itself and makes us hate ourselves for being alone. There is a reason that lack of social support triggers suicidal thoughts, and that is because when we don't have other people who by their very presence counter the assertions of our own negative thoughts as being alone and unloveable, it becomes more and more attractive to believe those negative thoughts are true.

There are some people who may be reading this and feeling upset. They are currently alone, or believe themselves to be alone, and hearing about how loneliness can worsen one's mental health may send them into negative thought spirals that in turn leave them feeling worse. It is important to note that I discuss this not to condemn those feeling alone to more unhappiness, but as a reminder that their mental health can be very much improved with the presence of others.

And there are multiple opportunities to connect with other people. We may be away from our friends, but we can meet and talk with new people. There are events going on around where we live, and even if there aren't, or none of them appeal to us, there are a wide range of communities online, filled with like-minded people whom we can spend time with. I say this knowing that some of my closest friends are people I met, and know primarily, through website forums and Facebook. Sometimes, the sheer attempt at connecting with other people can be helpful, because it acknowledges to us that we can work to change our situation.

That said, while relationships with other people are very helpful, some are more helpful than others, and some are not helpful at all, or even harmful. acquaintances who continually drain our energy (and other resources), who denigrate us or otherwise make us feel bad about ourselves, who fail to accept us for who we are, and who routinely violate our trust are all relationships that can take a toll on our already taxed mental faculties. Some acquaintances may not believe, as many people in our society do, that we do not have mental health issues, but that we are being "weak" or "selfish". With these people, it is best for us to keep ourselves at a distance. We need not necessarily end a relationship entirely, but we must learn to set boundaries that prevent them from hurting us.

Of course, even when we know our mental health can be improved by spending time with other people, it can be difficult to do so. We may have negative thoughts that lead us to believe we won't be able to enjoy ourselves with them, or that they won't want to spend time with us. Very often, this is not true. Very often, this is the result of our mental illness, and we need to fight against that. We often need to push ourselves into those social situations, even when we don't want to, or feel like we can. Often we surprise ourselves.

Though it may sometimes be hard to see, a great deal of our mental health is in our control. We can choose what we do and how we spend our time. We can choose to spend our time in ways that helps us get better. Spending time with other people, people who make us feel good and loved, is one of those ways, and may be one of the most crucial.

---

Further Reading

Social Support Is Critical For Depression Recovery

Everyone is alone sometimes. Sometimes we need to be by ourselves for a while. For people with good mental health, being alone is not that much of a problem. For someone who struggles with mental issues, excessive isolation can be very problematic.

We are social creatures. Most of us thrive and depend upon the companionship of other people. We enjoy spending time with them, and they help us feel loved, and valuable. Often, they help keep our demons at bay by their presence alone, their own voices counteracting our own self-critical or otherwise problematic voices.

In the absence of people we can enjoy ourselves with, the only things we have to keep ourselves company are ourselves. And sometimes, we don't give ourselves the best company. Critical and negative voices in our head routinely attempt to beat us down. Obsessions make themselves known in our idle thoughts. The sheer knowledge of our own loneliness folds in on itself and makes us hate ourselves for being alone. There is a reason that lack of social support triggers suicidal thoughts, and that is because when we don't have other people who by their very presence counter the assertions of our own negative thoughts as being alone and unloveable, it becomes more and more attractive to believe those negative thoughts are true.

There are some people who may be reading this and feeling upset. They are currently alone, or believe themselves to be alone, and hearing about how loneliness can worsen one's mental health may send them into negative thought spirals that in turn leave them feeling worse. It is important to note that I discuss this not to condemn those feeling alone to more unhappiness, but as a reminder that their mental health can be very much improved with the presence of others.

And there are multiple opportunities to connect with other people. We may be away from our friends, but we can meet and talk with new people. There are events going on around where we live, and even if there aren't, or none of them appeal to us, there are a wide range of communities online, filled with like-minded people whom we can spend time with. I say this knowing that some of my closest friends are people I met, and know primarily, through website forums and Facebook. Sometimes, the sheer attempt at connecting with other people can be helpful, because it acknowledges to us that we can work to change our situation.

That said, while relationships with other people are very helpful, some are more helpful than others, and some are not helpful at all, or even harmful. acquaintances who continually drain our energy (and other resources), who denigrate us or otherwise make us feel bad about ourselves, who fail to accept us for who we are, and who routinely violate our trust are all relationships that can take a toll on our already taxed mental faculties. Some acquaintances may not believe, as many people in our society do, that we do not have mental health issues, but that we are being "weak" or "selfish". With these people, it is best for us to keep ourselves at a distance. We need not necessarily end a relationship entirely, but we must learn to set boundaries that prevent them from hurting us.

Of course, even when we know our mental health can be improved by spending time with other people, it can be difficult to do so. We may have negative thoughts that lead us to believe we won't be able to enjoy ourselves with them, or that they won't want to spend time with us. Very often, this is not true. Very often, this is the result of our mental illness, and we need to fight against that. We often need to push ourselves into those social situations, even when we don't want to, or feel like we can. Often we surprise ourselves.

Though it may sometimes be hard to see, a great deal of our mental health is in our control. We can choose what we do and how we spend our time. We can choose to spend our time in ways that helps us get better. Spending time with other people, people who make us feel good and loved, is one of those ways, and may be one of the most crucial.

---

Further Reading

Social Support Is Critical For Depression Recovery

Monday, March 17, 2014

The Magic Cure

Not too long ago, I was convinced that by switching degrees, maybe even switching colleges, I would no longer be depressed.

The reasons at the time all came across as very logical to me: I was struggling with relationships among people of my own degree, and at my own college. I felt increasingly cynical about my degree, wondered if it would provide the career opportunities I wanted from it, if it would satisfy me. I became increasingly fearful that if I pursued this degree at this college, I would be unhappy and a failure.

In the light of that, the idea of transferring to another college to pursue another degree seemed attractively simple. From my perspective, the career prospects were better. I would be better fulfilled on this career path. I could get along better with the people pursuing that degree. I would succeed and be happy.

Then I told my therapist.

He pointed out to me that, in my enthusiasm for transferring, I did not think about the finer details. What sort of courses would I take? Would some of the courses I take be ones I would struggle with? I would be going to a new community surrounded by people I did not know. Even though I struggled at my current college, there were people there who knew and liked me. How would I deal with the isolation of being a second year transfer? Was I even fully aware of the demands that this career would have on me?

I hadn't thought of any of those things. As my therapist laid out these options everything became darker. Everything was frightening again. Everything was uncertain. And as I became more frightened and anxious, I realized just how fragile the illusion I built for myself had been. And it was an illusion. It was not a possible choice motivated by reason and contemplation, but by emotion and desperation. It may very well have been a good move, but the way I was thinking about it was not.

It has been almost a month since that episode. I am significantly calmer, and more at peace with my current choice of career and college, though there is still that uncertainty, which may indeed never go away. The problems I struggled with that motivated me to consider switching colleges and degrees are still here, and with time dulling the frenzied emotions, I recognize that even had I transferred, many of those problems would not go away, because those problems are in many ways internal, and very deep-rooted. I was searching for a solution that could come from outside, instantaneously, and easily.

I had been searching for a magic cure.

We've all searched for magic cures at some point in our lives. They can be hard to identify at times, but a good identifying mark is the phrase "if I just".

"If I just read the right book about dealing with my depression, I'll get better."

"If I just have a relationship with this person, I'll be happy."

"If I just leave home and go to college, all of my problems will be solved."

I have had all of these thoughts. Ultimately, I could either not achieve the "just's" I set for myself, or I achieved them and discovered they did not "just" solve my problems like I had hoped. I scoured countless advice books looking for that one bit of golden cure-all, and came up short. The relationships I wanted did not come about. I went to college, and discovered I had the same problems I did in high school.

That is not to say that such things were or would have been useless. Much of the advice I've found in my searching has been useful in learning how to cope with depressive episodes. Relationships can be fulfilling and its players mutually supportive of one another. College took me out of the stagnant environment of my then-current state as an unemployed high-school graduate and gave me direction in life and motivation to pursue that direction. They did not "just" solve anything, but they did or could help to push me towards better mental health.

Magic cures need not necessarily be about trying to change. Magic cures can also be about staying put and waiting for whatever problems to pass. This can be seen in abusive relationships, where battered victims tell themselves that what's happening to them will past, that their loved one will become nicer, or that the things making them angry will end. Magic cures are about achieving massive results without making ourselves too uncomfortable.

The problem with magic cures is not that what we're thinking as magic cures can't be helpful. They absolutely can. But when we view them as easy cure-alls, they encourage us to think they are all we need to do, and often that they can be done easily and quickly.

We underestimate the amount of effort that goes into them, and threaten to go into them ill-prepared for what we would face. If I actually went through with changing colleges without taking into consideration the things that my therapist pointed out, I would have been blindsided by them, and that could have made my depression worse.

We may feel like we can abandon other, more difficult tasks of self-improvement out of the belief that our one magic cure is all that we need to get better, and as a result we can obstruct our own recovery. They provide us a false hope that will only lead to disappointment when we discover our problems are more complex than a single act can solve.

More than that, magic cures can be dangerous. Magic cures often appear as some major shift in lifestyle or behavior, such as quitting a job or moving to a new town. They are attractive because they allow us to think our problems are caused primarily by external, passing things, rather than something more internal. And sometimes that is the case. An abusive and restricting household, for example, can cause a great deal of misery, and leaving that household for a more stable one can be helpful. Yet other times, we change places only to find that our problems have not disappeared but moved with us, and we are without the old support systems and coping techniques we had before.

The fact is, we can get better. But for most of us, it is not through a single act, but through a series of acts, performed consistently, sometimes begrudgingly, that bring us closer and closer to where we want to be. It can be difficult, but it is not impossible. To get there, we have to expend a lot of time, a lot of energy, and have a lot of hope. When we see something, anything, that promises to solve all of our problems, with seemingly minimal effort on our parts, we threaten to deceive ourselves, and obstruct our own recovery.

We must continually look for ways to get better, but sometimes we need to take a moment and ask ourselves what exactly we're looking to get from our decisions. We must make sure that we are not putting all of our hope in a single option, but continually looking to improve in as many ways as we can. Similarly, we have to be sure that when we make our decisions, we do them from a point of reasoned consideration, not one motivated by emotion alone.

The reasons at the time all came across as very logical to me: I was struggling with relationships among people of my own degree, and at my own college. I felt increasingly cynical about my degree, wondered if it would provide the career opportunities I wanted from it, if it would satisfy me. I became increasingly fearful that if I pursued this degree at this college, I would be unhappy and a failure.

In the light of that, the idea of transferring to another college to pursue another degree seemed attractively simple. From my perspective, the career prospects were better. I would be better fulfilled on this career path. I could get along better with the people pursuing that degree. I would succeed and be happy.

Then I told my therapist.

He pointed out to me that, in my enthusiasm for transferring, I did not think about the finer details. What sort of courses would I take? Would some of the courses I take be ones I would struggle with? I would be going to a new community surrounded by people I did not know. Even though I struggled at my current college, there were people there who knew and liked me. How would I deal with the isolation of being a second year transfer? Was I even fully aware of the demands that this career would have on me?

I hadn't thought of any of those things. As my therapist laid out these options everything became darker. Everything was frightening again. Everything was uncertain. And as I became more frightened and anxious, I realized just how fragile the illusion I built for myself had been. And it was an illusion. It was not a possible choice motivated by reason and contemplation, but by emotion and desperation. It may very well have been a good move, but the way I was thinking about it was not.

It has been almost a month since that episode. I am significantly calmer, and more at peace with my current choice of career and college, though there is still that uncertainty, which may indeed never go away. The problems I struggled with that motivated me to consider switching colleges and degrees are still here, and with time dulling the frenzied emotions, I recognize that even had I transferred, many of those problems would not go away, because those problems are in many ways internal, and very deep-rooted. I was searching for a solution that could come from outside, instantaneously, and easily.

I had been searching for a magic cure.

We've all searched for magic cures at some point in our lives. They can be hard to identify at times, but a good identifying mark is the phrase "if I just".

"If I just read the right book about dealing with my depression, I'll get better."

"If I just have a relationship with this person, I'll be happy."

"If I just leave home and go to college, all of my problems will be solved."

I have had all of these thoughts. Ultimately, I could either not achieve the "just's" I set for myself, or I achieved them and discovered they did not "just" solve my problems like I had hoped. I scoured countless advice books looking for that one bit of golden cure-all, and came up short. The relationships I wanted did not come about. I went to college, and discovered I had the same problems I did in high school.

That is not to say that such things were or would have been useless. Much of the advice I've found in my searching has been useful in learning how to cope with depressive episodes. Relationships can be fulfilling and its players mutually supportive of one another. College took me out of the stagnant environment of my then-current state as an unemployed high-school graduate and gave me direction in life and motivation to pursue that direction. They did not "just" solve anything, but they did or could help to push me towards better mental health.

Magic cures need not necessarily be about trying to change. Magic cures can also be about staying put and waiting for whatever problems to pass. This can be seen in abusive relationships, where battered victims tell themselves that what's happening to them will past, that their loved one will become nicer, or that the things making them angry will end. Magic cures are about achieving massive results without making ourselves too uncomfortable.

The problem with magic cures is not that what we're thinking as magic cures can't be helpful. They absolutely can. But when we view them as easy cure-alls, they encourage us to think they are all we need to do, and often that they can be done easily and quickly.

We underestimate the amount of effort that goes into them, and threaten to go into them ill-prepared for what we would face. If I actually went through with changing colleges without taking into consideration the things that my therapist pointed out, I would have been blindsided by them, and that could have made my depression worse.

We may feel like we can abandon other, more difficult tasks of self-improvement out of the belief that our one magic cure is all that we need to get better, and as a result we can obstruct our own recovery. They provide us a false hope that will only lead to disappointment when we discover our problems are more complex than a single act can solve.

More than that, magic cures can be dangerous. Magic cures often appear as some major shift in lifestyle or behavior, such as quitting a job or moving to a new town. They are attractive because they allow us to think our problems are caused primarily by external, passing things, rather than something more internal. And sometimes that is the case. An abusive and restricting household, for example, can cause a great deal of misery, and leaving that household for a more stable one can be helpful. Yet other times, we change places only to find that our problems have not disappeared but moved with us, and we are without the old support systems and coping techniques we had before.

The fact is, we can get better. But for most of us, it is not through a single act, but through a series of acts, performed consistently, sometimes begrudgingly, that bring us closer and closer to where we want to be. It can be difficult, but it is not impossible. To get there, we have to expend a lot of time, a lot of energy, and have a lot of hope. When we see something, anything, that promises to solve all of our problems, with seemingly minimal effort on our parts, we threaten to deceive ourselves, and obstruct our own recovery.

We must continually look for ways to get better, but sometimes we need to take a moment and ask ourselves what exactly we're looking to get from our decisions. We must make sure that we are not putting all of our hope in a single option, but continually looking to improve in as many ways as we can. Similarly, we have to be sure that when we make our decisions, we do them from a point of reasoned consideration, not one motivated by emotion alone.

Monday, March 10, 2014

Dance Alone Will Not Save You: What Silver Linings Playbook Gets Wrong About Mental Illness

Let me begin by getting this out of the way: The Silver Linings Playbook is a nuanced and sympathetic portrayal of the mentally ill. At parts.

For those who are not familiar with the film, The Silver Linings Playbook is about a man named Pat who struggles with bipolar disorder. Estranged from his wife after he had a violent episode upon discovering her with another man, he has spent eight months in treatment, and is now looking to reconcile with his wife despite his wife having moved on. On the way, he meets a woman named Tiffany, who also struggles with mental illness. They gradually grow closer together through their shared neuroses, and engage in a kind of social therapy through practicing together for an upcoming dance competition, yet Pat still struggles with his interest in Tiffany and his refusal to move on from his wife.

For those who are not familiar with the film, The Silver Linings Playbook is about a man named Pat who struggles with bipolar disorder. Estranged from his wife after he had a violent episode upon discovering her with another man, he has spent eight months in treatment, and is now looking to reconcile with his wife despite his wife having moved on. On the way, he meets a woman named Tiffany, who also struggles with mental illness. They gradually grow closer together through their shared neuroses, and engage in a kind of social therapy through practicing together for an upcoming dance competition, yet Pat still struggles with his interest in Tiffany and his refusal to move on from his wife.Had the film stayed like this, it would have been fine. The film contains stories which many of us can relate to. Stories of people who struggle with mental illness, stories of their family who struggle with their struggles. It makes headway by having a mentally ill protagonist who has been violent who is not defined by his violence and mental illness, but rather that it is one of many issues he struggles with, along a sense of abandonment, refusal to let go of the past, and a fear of further failure.

The problem is that, while it is many ways respectful of mental illness, in many ways it is also misleading, dishonest, and in some cases outright disrespectful of people with mental illness and the struggles they go through."

Here are the three big problems with Silver Linings Playbook:

Mental Illness Becomes "Cute"

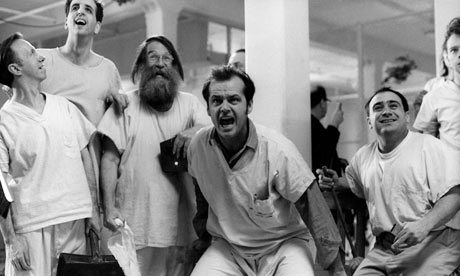

Since at least the time of "One Flew Over The Cuckoo's" nest, mental illness has been shown through a distorted, saccharine perspective, portraying those who have it as quirky or creative "free spirits" rather than sufferers of the debilitating and destructive force that mental illness is.

Pat often behaves in a very childlike manner, getting easily distracted and having over-the-top reactions to circumstances. He speaks in a fast-paced and stream-of-consciousness style, and while such a speaking style is a symptom of mania among people with Bipolar disorder, the film often focuses on it for comedic effect. Even though the disorder that leads to him acting like that is the same disorder that leads to him throwing a book out the window after he disagrees with how it ends.

Pat's father's OCD manifests primarily as an interesting quirk, mostly involving him having specific and arbitrary rituals while watching the football game. In reality, OCD in its most severe forms is extremely debilitating, and often those with it feel a compulsion to perform their ritual tasks over and over again even when they know they should not, and they often feel as if they have no control over much of their own lives. And while that shows up to some degree after the Eagles lose and Pat's father becomes very distressed, for the most part that harsh reality is downplayed in favor of portraying OCD in comedic terms. Even when Pat's father's OCD results in him betting all of his money on the outcome of the dance competition/football game at the end of the film, the ramifications of his untreated OCD are glossed over and it instead becomes a problem for Pat and Tiffany to solve.

What's odd is that these moments of "quirky" mental illness appear alongside much more nuanced and realistic portrayals of mental illness. The film that has Pat suffering a mental breakdown in the attic while his parents desperately try to soothe him is the same film where an increasingly irate and distressed Pat becomes immediately calm when he is distracted by his friend giving him an old Ipod. Pat's rapid stream-of-consciousness speaking exists alongside his unrealistic and damaging goals he sets for himself. Yet in both cases one of the situations is played for laughs while the other is viewed with concern, as though they were not both root of the same problem. The result is an inconsistent and overexagerrated portrayal of mental illness, where the viewer cannot always tell what is actually true mental illness, and what is exaggerated for filmic effect.

What's odd is that these moments of "quirky" mental illness appear alongside much more nuanced and realistic portrayals of mental illness. The film that has Pat suffering a mental breakdown in the attic while his parents desperately try to soothe him is the same film where an increasingly irate and distressed Pat becomes immediately calm when he is distracted by his friend giving him an old Ipod. Pat's rapid stream-of-consciousness speaking exists alongside his unrealistic and damaging goals he sets for himself. Yet in both cases one of the situations is played for laughs while the other is viewed with concern, as though they were not both root of the same problem. The result is an inconsistent and overexagerrated portrayal of mental illness, where the viewer cannot always tell what is actually true mental illness, and what is exaggerated for filmic effect.Most of the Mentally Ill Characters Are Violent

For a long time, films have portrayed the mentally ill as violent. We've all seen episodes of crime procedurals where the culprit is a someone "crazy", with untreated (or in some cases, treated) mental illness). While Silver Linings does take steps to not define the mentally ill characters by their violence, and humanizes them, it nonetheless portrays mental illness, for the most part, as accompanied by violent behavior.

Pat is sent to a mental health facility when he beats up the man his wife is having an affair with. Pat's father has a history of violence. Tiffany slaps, shouts, and destroys tableware over the course of the film. The one mentally ill character who is not violent is Chris Tucker's character, yet he has very little screen presence in the movie.

In reality, most people with mental illness are not violent, just as the majority of the general population is not violent. In fact, people with mental illness are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.

In fairness, violence is prevalent throughout film and television, not just in those with mental illness. It's an easy, concise, and visual way to make conflicts more interesting. It becomes much more palatable to show a divorced couple battling over alimony, for example, if you include a knife fight between their lawyers. Yet while in such a scenario that violence can be more easily accepted as Hollywood exaggeration, because we know such scenarios aren't so violent in real life, with mental illness it becomes much more problematic because many of us don't have those real life scenarios to compare it to. The end result is people see those crime procedurals, those murder mysteries, and even this film, with mentally ill characters that are violent, and they conclude that mentally ill people as a whole are just as violent.

The Ending Ignores The Mental Illness of the Characters

The most damning part of the film, however, isn't how it portrays the mentally ill and their issues, but how it sweeps those issues under the rug in favor of a typical Hollywood happy ending.

While the first two acts of the film have been about how Pat and Tiffany grow closer to each other and struggle with their mental illness, the third act of the film is about how the two have to work past their issues to score a five in the dance competition. At the end of the film, they score that five, and Pat and Tiffany become a couple, and the issue of their mental illness is not brought up to any significant extent again.

One of the possible themes for this film that I've heard is "Anyone can find love, even broken people and misfits", which is a good sentiment and all, but the film does not support that. Suppose you knew two people in real life, both mentally ill, who became a couple. Suppose they struggled with their mental illness and how their mental illness affected each other. Suppose that, instead of focusing on treatment and therapy for their illness, they instead invest their time and energy into winning a dance competition, and put any thoughts of therapy or treatment out of their head for the entirety of the time prior to this dance competition.

One of the possible themes for this film that I've heard is "Anyone can find love, even broken people and misfits", which is a good sentiment and all, but the film does not support that. Suppose you knew two people in real life, both mentally ill, who became a couple. Suppose they struggled with their mental illness and how their mental illness affected each other. Suppose that, instead of focusing on treatment and therapy for their illness, they instead invest their time and energy into winning a dance competition, and put any thoughts of therapy or treatment out of their head for the entirety of the time prior to this dance competition.

We would say they were ignoring the larger problem.

That's exactly what this film does. It ignores the larger problem of these characters and their issues. Both characters are still suffering from untreated mental illness (I say untreated because, though both characters take medication and therapy, the film downplays this and neither therapy or medication seem to have a substantial effect on their well-being), and the ending of the film implies that they will be in a closer relationship with one another. As anyone who has been in a relationship with someone with untreated mental illness knows, the effects are hard enough when there is only one person. Indeed, we've already seen this in the film with how Pat's wife had a restraining order put on him. The effects are multiplied when both people are mentally ill. These are two individuals who do not know how to cope with and control their mental illness, and both have a tendency for exaggerated, violent outbursts. If their story continues as it had, their relationship will end, and none of the possible endings will be happy.

It could be argued that the film isn't about providing a true portrayal of mental illness, that it is about other things. Yet if that is the case, why include mental illness? Is it meant simply as an interesting backdrop to a different story? Does mental illness deserve to be used as the backdrop to a story, especially when the film does not show a full understanding of mental illness?

Or does it turn mental illness into a caricature? Does it narrow the perspective on these people and view them solely in relation to other, more "important" issues? If a film uses something only to do a disservice to what that something actually is, it shouldn't be using it.

Monday, March 3, 2014

I went four days without Prozac. Here's what happened (and thoughts on taking medication)

This is a picture of my hand.

Note the torn skin. That is the result of when I had my fist tightened for thirty minutes on Tuesday.

I was immensely distressed at the time. To give context, I had an essay paper due on Thursday. 10 to 12 pages, double-spaced. I had six pages, and at the time, I could not figure out an additional four. On a large scale, such a problem is relatively inconsequential, and normally I'm sure I would have figured out a solution. Yet I could not get my worries and frustrations out of my head, and it led to this, along with an impulse to self-injurious behavior (head hitting, scratching, etc.). There was a period of time where I broke down crying for upwards of half an hour.

For greater context, I had run out of Prozac several days prior, and this was the day I finally got a new batch. It took another two days before I was back to normal.

I don't think it's a stretch to believe that this was caused by me running out of my medication, and that it ended in part because I got back on it.

The effects of medication differs for each of us and for every medication. But if we are taking medication it is imperative that we stay on it, unless our doctors tell us otherwise. We cannot know the proper effects of our medication unless we are taking it properly.

That said, there are many concerns and fears about taking medication that I feel should be addressed. A lot of them are addressed very well in this New York Times article, and I would encourage everyone with concerns about medication to read it. I cannot add any further to it except in terms of my own experience.

It can be difficult to ascertain the effectiveness of medication in your our life. In part because if things are going well, we often don't think to reflect on why they are. When I found out I had run low on medication, I was initially unbothered by it. I thought I could easily manage without it, in part because I had been so used to living with medication, that I couldn't imagine being without it as well. Yeah, I was wrong.

I'd had similar events in my past, where I thought it wouldn't be a problem to go off of medication until I initially went off of it. Thankfully it's resolved within a few days after I return to my medication, but it helps to remember that I am taking that medication for a reason.

When I was without Prozac, a lot of anxieties I had prior were magnified to a great extent. My future shortened before my eyes the more I thought of it. It says something that when I called my therapist during distress, that when I got to that I had been several days without Prozac, he emphasized that part above all else. And for good reason. Medication is integral to my continued mental health. It is not for everyone, but it is for me.

A few final thoughts on medication. I'd like to point out that two very common problems with medication. that of forgetting to take it on schedule, and of forgetting to refill it. Here are solutions that have worked for me:

With forgetting to take medication on schedule, it helps to place your medication in a place see every day. On a bathroom cabinet so that you see it whenever you use the restroom, for example. Or on a kitchen counter so you see it when making meals. For my part, I take my medication in the morning, and put my medication on my dresser so that I see it when I get dressed. Similarly, daily alarms can also be useful for remembering when to take medication.

With forgetting to refill medication, it helps to leave reminders ahead of time. My prescription needs refilled every ninety days, so I set a reminder for myself that after two months I am alerted that I need to refill my medication, and then take the steps so that it is refilled on time.

Finally, many people concerned about medication are worried about the side-effects of medication, and that it may not be effective. It is important to remember that medication is effective for a significant number of people, and you may very well be one of those people to whom it can benefit. The only way to find out is by taking it as prescribed by your doctor.

As far as side-effects go, it is very easy to find a list of common side-effects to medication. Remember that taking medication doesn't necessarily guarantee any or all of the possible side-effects. Even if you do have side-effects from the medication, that does not itself mean it is ineffective, or that you shouldn't be taking the medication. In some cases, it is a matter of balancing the benefits and drawbacks of the medication and determining whether or not you are willing to take the side-effects in exchange for the benefits.

Again, consult your doctor before taking any medication. And consult your doctor if you are thinking of making changes to your existing medication. Medication can be very useful in helping us get better, but it is important to approach medication as informed as we can be.

Note the torn skin. That is the result of when I had my fist tightened for thirty minutes on Tuesday.

I was immensely distressed at the time. To give context, I had an essay paper due on Thursday. 10 to 12 pages, double-spaced. I had six pages, and at the time, I could not figure out an additional four. On a large scale, such a problem is relatively inconsequential, and normally I'm sure I would have figured out a solution. Yet I could not get my worries and frustrations out of my head, and it led to this, along with an impulse to self-injurious behavior (head hitting, scratching, etc.). There was a period of time where I broke down crying for upwards of half an hour.

For greater context, I had run out of Prozac several days prior, and this was the day I finally got a new batch. It took another two days before I was back to normal.

I don't think it's a stretch to believe that this was caused by me running out of my medication, and that it ended in part because I got back on it.

The effects of medication differs for each of us and for every medication. But if we are taking medication it is imperative that we stay on it, unless our doctors tell us otherwise. We cannot know the proper effects of our medication unless we are taking it properly.

That said, there are many concerns and fears about taking medication that I feel should be addressed. A lot of them are addressed very well in this New York Times article, and I would encourage everyone with concerns about medication to read it. I cannot add any further to it except in terms of my own experience.

It can be difficult to ascertain the effectiveness of medication in your our life. In part because if things are going well, we often don't think to reflect on why they are. When I found out I had run low on medication, I was initially unbothered by it. I thought I could easily manage without it, in part because I had been so used to living with medication, that I couldn't imagine being without it as well. Yeah, I was wrong.

I'd had similar events in my past, where I thought it wouldn't be a problem to go off of medication until I initially went off of it. Thankfully it's resolved within a few days after I return to my medication, but it helps to remember that I am taking that medication for a reason.

When I was without Prozac, a lot of anxieties I had prior were magnified to a great extent. My future shortened before my eyes the more I thought of it. It says something that when I called my therapist during distress, that when I got to that I had been several days without Prozac, he emphasized that part above all else. And for good reason. Medication is integral to my continued mental health. It is not for everyone, but it is for me.

A few final thoughts on medication. I'd like to point out that two very common problems with medication. that of forgetting to take it on schedule, and of forgetting to refill it. Here are solutions that have worked for me:

With forgetting to take medication on schedule, it helps to place your medication in a place see every day. On a bathroom cabinet so that you see it whenever you use the restroom, for example. Or on a kitchen counter so you see it when making meals. For my part, I take my medication in the morning, and put my medication on my dresser so that I see it when I get dressed. Similarly, daily alarms can also be useful for remembering when to take medication.

With forgetting to refill medication, it helps to leave reminders ahead of time. My prescription needs refilled every ninety days, so I set a reminder for myself that after two months I am alerted that I need to refill my medication, and then take the steps so that it is refilled on time.

Finally, many people concerned about medication are worried about the side-effects of medication, and that it may not be effective. It is important to remember that medication is effective for a significant number of people, and you may very well be one of those people to whom it can benefit. The only way to find out is by taking it as prescribed by your doctor.

As far as side-effects go, it is very easy to find a list of common side-effects to medication. Remember that taking medication doesn't necessarily guarantee any or all of the possible side-effects. Even if you do have side-effects from the medication, that does not itself mean it is ineffective, or that you shouldn't be taking the medication. In some cases, it is a matter of balancing the benefits and drawbacks of the medication and determining whether or not you are willing to take the side-effects in exchange for the benefits.

Again, consult your doctor before taking any medication. And consult your doctor if you are thinking of making changes to your existing medication. Medication can be very useful in helping us get better, but it is important to approach medication as informed as we can be.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)